China Change

Yaxue Cao, March 21, 2018

Continued from The Might of an Ant: the Story of Lawyer Li Baiguang (1 of 2)

Rights Movement Spread All Over the Country

By 2004, Zhao Yan and Li Baiguang were under constant threat. Fuzhou police told the village deputies that Zhao and Li were criminals, and demanded that the deputies expose the two. The Fujian municipal government also dispatched a special investigation team to the hometowns of Li and Zhao to look into their family backgrounds. A public security official in Fu’an said: “Don’t you worry that Zhao and Li are still on the lam — that’s because it’s not time for their date with the devil just yet. Just wait till that day comes: we’ll grab them, put them in pig traps, and toss them into the ocean to feed the sharks!”

On September 17, 2004, Zhao Yan was arrested by over 20 state security agents while at a Pizza Hut in Shanghai. At that point he had already left the China Reform magazine and was working as a research assistant in the Beijing office of The New York Times. He was accused of leaking state secrets, denied a lawyer for several months, and eventually sentenced to three years on charges of fraud.

|

| Front row from left: Chen Yongmiao (陈永苗), Li Baiguang (李柏光), Fan Yafeng (范亚峰), Guo Feixiong (郭飞雄), Gao Zhisheng (高智晟); Back row from left: Teng Biao (滕彪), Pu Zhiqiang (浦志强), Wang Yi (王怡), Mo Shaoping (莫少平), Liu Xiaobo (刘晓波), Yu Meisun (俞梅荪), and Wang Guangze (王光泽). 2005. |

On December 14, 2004, Li Baiguang and three lawyers, while on their way to Fu’an to handle a rights defense case that was likely a trap, were hemmed in by police vehicles and arrested. Li was accused of illegally providing legal services, because he did not possess a law license. On the evening of December 21, a dozen police officers from Fu’an broke into Li’s apartment in Beijing, pried open his cabinets, and confiscated his hard drives and documents related to dismissing officials.

Thanks to the efforts of his friend Yu Meisun and a host of liberal intellectuals and journalists, Li Baiguang was released on bail after 37 days in custody. December to January are the coldest months of the year in Fujian, and there was no heating. In a cell with dozens of people, Li Baiguang recalled later, “I wore a suit, and it was cold. As a form of punishment, they told the cell boss to make me bathe in freezing seawater every day. I lost a lot of hair, and lost so much weight that my cheekbones protruded. When I came out my nephew hardly recognized me.”

The removal of officials between 2003 and 2004 was one of the key campaigns that initiated the rights defense movement, and one of the largest-scale rights defense activities in China. Around the same time, rights defense initiatives took place. During the Sun Zhigang (孙志刚) Incident in March 2003, three Peking University law PhDs, Xu Zhiyong (许志永), Yu Jiang (俞江) and Teng Biao (腾彪) wrote a letter to the National People’s Congress, demanding that they conduct a constitutional review of the law “Administrative Measures for Assisting Vagrants and Beggars with No Means of Support in Cities” (《城市流浪乞讨人员收容遣送办法》). He Weifang (贺卫方), Xiao Han (萧瀚), He Haibo (何海波), and two other well-known legal scholars demanded that the NPC conduct an investigation into how the ‘administrative measures,’ commonly known as ‘custody and repatriation,’ were actually being implemented. Gao Zhisheng began defending Falun Gong practitioners in court, demanded that the government respect freedom of belief, and called for the torture against practitioners to cease. Numerous other lawyers and legal scholars also began taking up human rights defense cases, bringing them to public consciousness. Other notable cases of the period included the defence of Hebei private entrepreneur Sun Dawu (孙大午), who was accused of ‘illegal fundraising’; the case of injured investors in the Shanbei oil fields; the case of Christian Cai Zhuohua (蔡卓华) who was arrested for printing the Bible; the Southern Metropolis Daily editor and manager Cheng Yizhong (程益中) and Yu Huafeng (喻华峰) who were punished for reporting on the Sun Zhigang case and broke the news of SARS; the ‘Three Servants’ religious case that involved hundreds of believers; the libel case against the authors of the Survey of Chinese Peasants (《中国农民调查》), and other incidents.

In fall of 2003 Xu Zhiyong, Teng Biao, and Zhang Xingshui (张星水) founded the organization Sunshine Constitutionalism (阳光宪政) in Beijing, later changing its name to the Open Constitution Initiative (公盟). Gongmeng, as it’s often known per the Chinese title, became a hub — and incubator — for human rights lawyers and legal activists. They held a meeting nearly every week, and Li Baiguang was one of the regular participants.

In the winter of 2003 there was an upsurge in the participation of independent candidates in People’s Representative elections in Beijing, and a number of these candidates were successful.

Many independent NGOs focused on environmental protection, AIDS control and prevention, women’s rights, and disabled rights, had sprung up in Beijing and other cities. They used the law and advocacy to propagate rights awareness.

Entering 2005, the dismissal of officials in Taishi Village (太石村), Guangdong Province, as well as the Linyi Family Planning Case in Shandong (临沂计生案), became public events involving lawyers, public intellectuals, and citizen activists from around the country.

|

| In Taishi Village in Guangdong, Guo Feixiong assisted the villagers’ effort to village head for embezzlement of public fund. |

At the end of 2005, Hong Kong’s Asia Weekly magazine highlighted 14 human rights lawyers and legal scholars, including Li Baiguang, as 2005 People of the Year.[1] It said that “these 14 rights defense lawyers aren’t afraid of power; they wield the constitution as a weapon, harness the power of the internet, and work to defend the rights of the 1.3 billion Chinese people granted in their own constitution, while pushing for the establishment of democracy and rule of law in China.” In the ensuing years, with the exception of one or two, these 14 lawyers and scholars would be arrested, tortured, disappeared, disbarred, or forced into exile. Still, the grassroots rights defense movement they helped to kick off would continue to expand, and gain new energy in the age of social media. We shall not elaborate on that here.

‘Turning into an Ant’

In late July 1999, after publishing Samuel Smiles’ “The Huguenots in France” (issued under the Chinese title “The Power of of Faith” 《信仰的力量》) , Li Baiguang went to a church in the Haidian district of Beijing, bought a copy of the Bible, and began to read it. In January 2005 after he was released from prison, he began attending the Ark Church in Beijing (北京方舟教会) to study the Bible and pray. The Ark Church was a meeting place for many dissidents, rights lawyers, Tiananmen massacre victims, and petitioners — and for this reason the house church suffered regular harassment by the police. On July 30, 2005, Li was baptized in a reservoir in Huairou (怀柔), Beijing. He loudly proclaimed his witness, telling of the several times in his life when he brushed shoulders with death. He spoke of the time that an inner voice told him to stop, as he was considering plunging to his death from a building at university. He told of the catastrophes he escaped in 1998, 2001, and then in 2004. He spoke of the cumulative impact that Samuel Smiles’ books had on him, and, finally, he expressed his gratitude to Jesus.

He began to tremble violently as he read, and only after the baptism was complete and he had sat down a while did it subside.

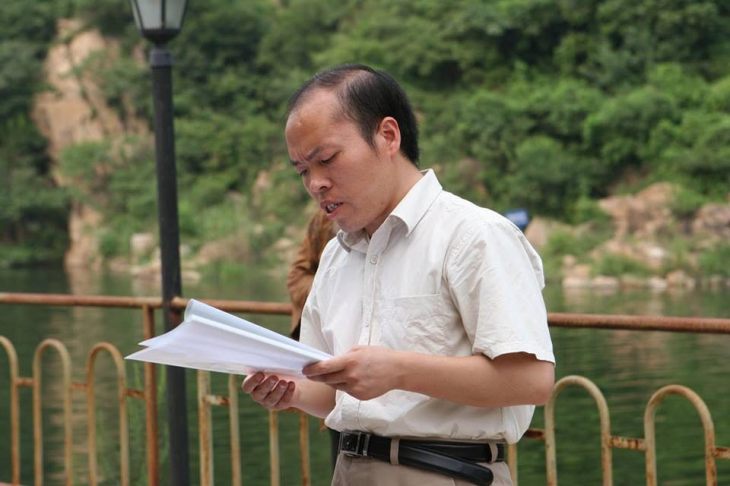

|

| Li Baiguang read aloud his testimony before being baptised in July 2005. |

For Li Baiguang, the freedom of the mind and soul and political freedom are simply two sides of the same coin. In 2000, while translating Smiles, Li wrote an essay titled “The Fountainhead of Modern Freedom is the Freedom of Individual Conscience” (《现代自由的源头是个体的良心自由》). He came to believe that only faith can shape and form conscience, and further, that the emergence of individual conscience is the origin and basis of freedom. This also makes it the source of the courage and motivation to fight for freedom and against despotism. He doesn’t believe that the widespread failure of Chinese to distinguish right and wrong, and the country’s moral decay, can be laid entirely at the feet of the Communist Party’s dictatorship.

In April 2006, in a session of “The Middle Forum” (《中道论坛》) with Fan Yafeng, Chen Yongmiao (陈永苗), and Qiu Feng (秋风), Li said he was tired of liberal intellectuals’ decades-long discussions of grand themes like constitutional governance, reform, and future China. He described his own turning point of involvement in actual, real life rights defense work. Of the eight years between 1997 and 2005, he said, he too spent the first five focused on all sorts of macro abstractions. “Recently I’ve had a realization: I’m willing to become an ant. I want to take the rights and freedoms in the books and, through case after case, bring them into the real world bit by bit. This is my personal stance. The path to this is legal procedure. In summer, the ant gathers food. Today, I’m also transporting food under the framework of rights defense, and in doing so accumulating experience and results for the arrival of the day of constitutional government.”

“According to the principles of political mechanics, it’s impossible to change minds overnight in such a large system. All you can do is loosen the screws one by one and turn the soil over clump by clump,” he said. Li held high hopes in the future of the nascent rights defense movement, and the gradual dismantling of autocracy from the margins. He thought that the rights defense movement would be crucial to China’s future establishment of a constitutional democracy.

This was the first time he proposed the ‘ant’ idea. In the years afterward, this is how he characterized his work and it became very familiar to his friends.

In May 2005, the Midland, Texas-based NGO China Aid, as well as the Institute on Chinese Law & Religion[2], invited seven Chinese rights lawyers and legal scholars to join a “China Freedom Summit.” Among those invited, Gao Zhisheng, Fan Yafeng, and Zhang Xingshui were blocked from leaving China; Li Baiguang, Wang Yi, Yu Jie, and Guo Feixiong were able to make it to the United States. Li Baiguang delivered a speech at the Hudson Institute titled “The Legal Dimensions of Religious Freedom: Reality and Prospects in China.” It proposed a systematic approach for defending religious freedom according to the law in China, and included the following actions:

- Submit an application to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress for constitutional review of laws, regulations and policies related to freedom of religious belief, and demand the annulment of unconstitutional laws that infringe upon religious freedom;

- Apply for religious services for prisoners in detention centres, prisons, and re-education camps in China who believe in God, or have come to believe while in detention, and send the gospel of Jesus Christ to all of the above detention facilities;

- Provide relief to Christians whose religious freedom has been infringed upon by agents of the state;

- Provide restitution to Christians who have had their persons or their residences illegally searched by agents of the state;

- Provide restitution to Christians who are being subjected to re-education through forced labor;

- Provide restitution to Christians or Christian organizations who have been punished with large fines;

- Provide restitution for those who have been harmed by the dereliction of duty of state organs.

On May 8, while at the Midland office of China Aid for one week of Bible study, the group learned that they would be granted a meeting with President Bush in the White House. On the morning of May 11, President Bush met with Yu Jie, Wang Yi, Li Baiguang, China Aid director Bob Fu, and Institute on Chinese Law & Religion director Deborah Fikes, in the Yellow Oval Room.

Li Baiguang presented President Bush with a gift — a copy of a proposal to make a documentary titled “American Civilization.” It was exquisitely designed by the artist Meng Huang (孟煌). In 2003, Li and his intellectual friends in Beijing designed together two major documentary projects. One of them was a 30-episode series that would introduce the democratic experience in 30 countries. Another, “American Civilization,” would be a 100-episode documentary series that would provide Chinese people a comprehensive introduction to the establishment of America, including its political life, its judicial system, education system, and religious beliefs. “I want to make it a television special for the education of the public,” Li said. He established the Beijing Qimin Research Center (北京启民研究中心) to push the plans forward, but in the end the two ambitious projects were aborted.

The three Christians from China being received by President Bush was, at the time, a major news story. But for the ten years following, the meeting with the U.S. President was remembered more for a controversy that surrounded it: the so-called “rejecting Guo incident.” This is a reference to the fact that Guo Feixiong was excluded from the meeting, purportedly by Yu Jie and Wang Yi, who argued that the meeting was for Christians only and Guo should not attend because he was not a Christian. Later, Li Baiguang expressed his regret that this had taken place. He told rights defense lawyer Tang Jitian (唐吉田) that if it didn’t occur, along with the enormous acrimony around it, the different groups in Chinese civil society might have been more unified and stronger.

Also during this trip to the U.S., Li was invited by Bob Fu to be China Aid’s legal consultant. When Li returned to China, he said in a 2010 interview, apart from his regular rights defense work, he “traveled across the country to provide legal support to persecuted house churches.” Li partnered with China Aid in this fashion until his death.

During that same period, Li sat the bar, passed, and became a lawyer. In December 2007 he hung his shingle with the Common Trust Law Firm (共信律师事务所) in Weigongcun, near Peking University.

In June 2008, Li and six other Chinese dissidents and rights lawyers were awarded the National Endowment for Democracy’s Democracy Award.

Law Career

Li Baiguang was among the 303 initial signatories of Charter 08. But after that point he gradually retired from the media and public spotlight. “Although the substance of my rights defense work has not changed,” he said in the 2010 interview, “my methods are more low-key and moderate than before. I no longer write articles attacking and castigating the authorities; all I want to do now is actually see implemented the laws that they themselves wrote, and win for victims the rights and freedoms that they should enjoy.”

|

| Reading case files with colleagues in Fuzhou, 2017. |

Over the following years Li, as a lawyer, left his footprints in every Chinese province except Tibet, acting as defense counsel in several hundred cases of persecuted Christians. The cases he was involved in include: the Shanghai Wanbang Church in 2009 (上海万邦教会), petitioning for Uighur church leader Alimjan Yimiti (阿里木江) in 2009, the 2010 Guangzhou Liangren Church case (广州良人教会), the 2010 Shuozhou Church case in Shanxi (山西朔州), the 2012 Pingdingshan Church case in Henan (河南平顶山) , the 2014 Nanle case (南乐), and the Cao Sanqiang (曹三强) case in 2017, among others.

As for the result of defending house churches, Li Baiguang summed it up in 2010 as follows: “If we look at the outcome of the administrative review of every rights case, the judgment has ruled against the church almost without exception. But later, I found a very strange phenomenon: after the conflict dies down, looking back a year later, we find that the local public security and religious bureaus no longer dare storm and raid these house churches, and congregants can meet freely. Using the law as a weapon to defend religious freedom works. Where we’ve fought cases, churches and religious activities in the area have since been little disrupted.”

While he was engaged in all this, Li also held rights defense training sessions for house churches around China. According to Bob Fu, director of China Aid, over the last roughly ten years, Li has trained several thousands people; the most recent was in January 2018 in Henan — conducted while he was lying on his back after he injured his leg, as church leaders from the local district gathered around to hear him discuss how they should defend their rights according to the law.

|

| Training barefoot lawyers. |

Between 2011 and 2013, Li taught in a number of training sessions for “barefoot lawyers” under the aegis of the “Chinese Urgent Action Working Group” (中国维权紧急援助组). In 2016 he also helped with a workshop for independent candidates for People’s Deputies elections. The Chinese Urgent Action Working Group is an NGO founded by the Swede Peter Dahlins, American Michael Caster, and rights lawyer Wang Quanzhang in 2009, offering legal training to rights defense lawyers and funding cases.

Li was extremely dedicated and hardworking, according to Dahlins. He focused on details, followed guidelines, and was always a long term thinker. Dahlins often joked with Michael Caster that Li Baiguang, who had met presidents and prime ministers, dressed and looked like a peasant.

Li also took part, with other human rights lawyers and activists, in trainings on the United Nations’ human rights mechanisms in Geneva under the aegis of Chinese Human Rights Defenders (维权网), an NGO that promotes human rights and rule of law in China.

Most residents in the town are Christians, Li Baiguang told friends. The community built its own kindergarten and elementary school, vegetable gardens, and sports pitch. “I felt like they built their own little Shangri-La,” Yang Zili said.

The Jianxi Church (涧西教会) that Li was associated with is the largest in the area, with around 200 stable congregants, most of whom were like Li: well-educated, having moved permanently to the village from elsewhere in China. For weekend church service, parishioners and catechumen (gradual converts) came from Zhejiang, Shanghai, Anhui and elsewhere, packing the church to the rafters. For these reasons, the church came to be watched closely by local religious affairs officials.

‘The night is nearly over; the day is almost here’

Li Baiguang was not part of any of the public incidents that have been brought to national attention by activists and netizens since 2008. In the mass arrests during the Jasmine Revolution of 2011, Li was not among them. When the New Citizens Movement became active between 2012 and 2013 and activists held regular dinner events, Li did not get involved. He wasn’t even part of the Chinese Human Rights Lawyers Group (人权律师团), founded in 2013. The 709 mass arrests of human rights lawyers didn’t implicate him, though for a while he signed up for being a defense counsel for 709 detainee lawyer Xie Yanyi. Numerous human rights lawyers have been barred from leaving the country; Li, on the other hand, traveled back and forth to America at will from 2006 to 2018.

Even when he was given trouble by police and state security, he did his best not to go public with it.

Per his own assessment in 2010, the authorities were “tolerating me to a much greater degree.” But his state of hypervigilance tells another story. A friend, Zheng Leguo (郑乐国), said that whenever he was with Li Baiguang in public places, Li would quickly scan his eyes over everyone in the vicinity to detect anything out of order. He was extremely careful about what he ate. When they ate at McDonalds, Li chose a table near the door, that way he could see people coming in and going out, and he could also escape at a moment’s notice if need be.

For Li Baiguang, 2017 was a disturbing year.

In January, he traveled to Washington, D.C. for the 15th anniversary of China Aid held at the Library of Congress. It was an invitation only event. During his remarks, Li said that apart from the suppression of civil society and human rights lawyers, attacks against house churches were also getting more severe. “From this point forward, human rights in China will enter its darkest period.” He added that rights defenders in China would use their God-given wisdom and intelligence to promote human rights, democracy, and the rule of law; he also called on the international community and NGOs to do what they could to help. “The night is nearly over; the day is almost here,” he said, citing Romans 13.

Li’s remarks were somehow leaked, according to Bob Fu, and reached the Chinese authorities — when Li returned home was treated “with severity.”

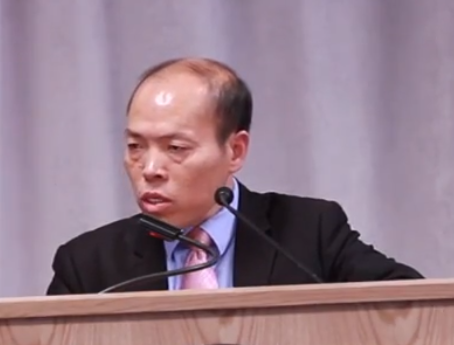

|

| Li spoke at the 15th anniversary of China Aid in January 2017. |

On October 17, 2017, a case Li was defending, involving seafood farmers in Wenling, Zhejiang, suing the government for malfeasance, went to trial. In the evening as Li was returning to his hotel, he was abducted by a dozen unidentified men. They took him to a forest and worked him over. They slammed their fists into his head and ordered him to leave the city by 10:00 a.m. the next morning, or else they would decapitate him and cut off his hands and feet. “When he mentioned that kidnapping,” Bob Fu said, “it was the most frightened I had seen him. The incident shook him badly.”

Another case Li took on in 2017 involved the apparent murder of a certain Pastor Han, of Korean ethnicity, in Jilin, northeastern China. Han was a pastor in the Three-Self Patriotic Movement who provided aid to North Korean refugees, and encouraged them to return to North Korea and spread the Gospel. It appeared that he was assassinated by North Korean operatives.

Towards the end of the year, Li met with the Beijing-based AFP journalist Joanna Chiu. After they met in a Starbucks, Li led her out into a small alley, across the street, and into another coffeeshop in order to avoid surveillance. He told Ms. Chiu how he’d been beaten, and also the suspicious death of the pastor.

In early February 2018, Li was invited to the National Prayer Breakfast, an annual event dedicated to the discussion of religion in public life, attended by thousands, including the U.S. president, policymakers, and religious and business leaders. Bob Fu, in an interview with VOAafter Li’s death, said that when Li was in the U.S. from February 5-11, the pastor of Jianxi Church was questioned about the whereabouts of Li and what he was doing in the United States. After he got back to China, he spoke with Fu twice, explaining that he was being investigated, and that danger felt imminent.

At 3:00 a.m. on February 26, 2018, Li Baiguang died in the Nanjing No. 81 PLA Hospital. In response to the widespread shock and suspicion, his family announced that he had died of late-stage liver cancer.

Coda

The death of Li Baiguang, like the death of Liu Xiaobo seven months ago, brings with it a momentous sense of ending. The PRC’s neo-totalitarian state grows more complete by the day; the discourse of political reform represented by Charter 08, and the rule-of-law trajectory sought by the rights defense movement, have hit a wall. Neither have room to expand. One by one, little by little, opportunities for further progress have been sealed and nixed. Truly, a ‘new era’ in China has begun.

The night is long; the worst is yet to come. Li Baiguang has died, like Liu Xiaobo, like Yang Tianshui, like Cao Shunli and all those who have fallen in the dark, but they live on; they are sparks of fire in the journey through night.

[1] They are Xu Zhiyong, Gao Zhisheng, Teng Biao, Pu Zhiqiang, Mo Shaoping, Li Baiguang, Zheng Enchong, Guo Feixiong, Li Heping, Fan Yafeng, Zhang Xingshui, Chen Guangcheng, and Zhu Jiuhu (许志永、高智晟、滕彪、浦志强、莫少平、李柏光、郑恩宠、郭飞雄、郭国汀、李和平、范亚峰、张星水、陈光诚以及朱久虎).

[2] The Institute on Chinese Law & Religion was registered in Washington, DC. It is now inactive.

ChinaAid Media Team

Cell: +1 (432) 553-1080 | Office: +1 (432) 689-6985 | Other: +1 (888) 889-7757

Email: [email protected]

For more information, click here