ABC News Broadcast: 17/05/2011 Reporter: Stephen McDonell

From the sole novice Daoist monk honing his Taiqi skills on top of a stunning sacred mountain, to the teeming underground Christian churches of the crowded south, Stephen McDonell takes a journey through China’s incredibly diverse spiritual renaissance. And he finds that wherever you go in this booming nation these days, there’s a deep hunger and a passion for something more than material prosperity.

In the city of Wenzhou despite secret police looking on, a 70 year old pastor agrees to be interviewed, conscious of the very real risks.

“Now we have nothing to be afraid of …. because God is with us.” – Pastor Zheng Datong

He’s been imprisoned before for his beliefs – but that hasn’t made him waver in his convictions. But it is enough for him to protect his congregation from being exposed. Filming is out of the question.

And he’s right to be concerned. The Chinese government has become increasingly worried about any threat to the ‘social harmony’ – and the revolutions and unrest in the Middle East have kicked those concerns into high gear. Lawyers, bloggers, artists, anyone with the potential to challenge the central authority, have all been targeted – harassed, arrested or even disappeared.

Even Bob Dylan on his recent concert tour of China had to agree to refrain from singing songs like The Times they are a Changing and Blowing in the Wind due to official fears they could incite unrest.

It’s not so surprising, then, that in such a climate the unofficial evangelical churches, with their millions of adherents, are being singled out. And little wonder that reporting on those churches would attract the attention of the secret police.

It was only by avoiding normal phone or email contact that Stephen McDonell managed to meet the doyen of China’s growing evangelist movement, Samuel Lamb. Pastor Lamb has already spent much of his life in strife over his beliefs – but he relishes the heavy hand of authority.

“Oppression, then more believers. Oppression then more believers. We aren’t afraid because we know oppression simply leads to more believers.” – Pastor Samuel Lamb

As China opened up after Mao, the ban on religions was also lifted – and there has been a resurgence of faiths of all kinds from Christianity and Buddhism to Daoism the religion that’s given spiritual succour to Chinese for thousands of years. It doesn’t seem to matter which God, the need to believe is stronger than ever.

“Gods exist when you believe in Gods truly” – Daoist Pilgrim

The question is, can the State accept the idea that many of their citizens follow the word of their gods above the word of the Party?

____________________________________

Transcript

MCDONELL: Dawn drumming on Wudang Mountain calls the

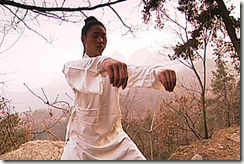

(Photo: A solitary monk practises taiqi on Wudang mountain)

For hundreds of years religious practices here have been favoured by emperors and paupers alike, not only for spiritual nourishment but because on Wudang Mountain, Daoism goes hand in hand with Kungfu.

MASTER ZHONG YUNLONG: “It’s about personal spirit – which means a person’s essence. It conquers the unyielding with the yielding. As far as we’re concerned, we love martial arts”.

MCDONELL: Zhong Yunlong started learning Kungfu when he was thirteen. Like other Daoist monks, his current age is a secret but he’s certainly not young any more. He says for powerful Kingfu the body is not enough, you need religion.

MASTER ZHONG YUNLONG: “Physical strength will be lost when a person reaches a certain age. Muscles will shrink and blood circulation will slow down but when martial arts are combined with religion they’ll keep developing at any age”.

MCDONELL: But the practices here said to enrich Kungfu were nearly lost during the Cultural Revolution in the 1970s. For a decade religion, other than the worship of Chairman Mao Zedong, was prohibited. When China opened up again in the 1980s, granting its people wider freedoms, Zhong Yunlong was one of the first Daoist believers who came to Wudang Mountain to become a monk.

MASTER ZHONG YUNLONG: “Gradually, since the opening up, people have begun to know about Daoism again”.

MCDONELL: According to this belief system, tranquillity brings wisdom and energy and this will in turn deliver a long and healthy life. In recent times, more and more Chinese people are travelling to Wudang Mountain in pursuit of these ideals. Many make the pilgrimage to its most holy site at the mountain peak.

To come to these mountains and walk up here does take a level of effort, but whether you’re a believer or not, a key reason for doing it is simply to see this old and mysterious place.

In the heavily worn steps of their forefathers, Chinese people are again scaling the mountain in order to reach the shrine of Zhen Wu Da Di. He was a local prince who’s said to have achieved the status of a god when he leapt off the mountain more than three thousand years ago.

WOMAN: (at shrine) “I’m a believe in Daoism. For example, it can nurture my body and spirit”.

MCDONELL: “Can it?”

WOMAN: “Yes”.

MCDONELL: “So it can really help you?”

WOMAN: “Absolutely. Gods exist when you believe in the Gods truly”.

MAN: (at shrine) “When a person is wealthy himself he can come here to pray for blessings on his parents’ safety and his children’s success and fame”.

MCDONELL: China once had Communism as a guiding principal, but as the country has now pretty well abandoned it, many people are looking for something to fill the void. For others, it is simply because they’re inquisitive. Either way, Daoism, Buddhism and Islam have all seen a significant increase in believers.

But there’s been one religion in particular which has experienced phenomenal growth and the real level of participation is not even known.

The Chong-yi Church in Hangzhou is the biggest Chinese Christian church in the world. On the day we visit there are around 5,500 worshippers here, but this building can hold 10,000 people if they squeeze in shoulder-to-shoulder.

PASTOR JOSEPH GU: “When this church started being used in 2005 we had fewer than 2,000 Christians. Now we have over 8,000. That’s a four fold increase”.

MCDONELL: Senior Pastor Joseph Gu runs this very model of a modern evangelical church. They’re cashed up with booming attendance figures and riding a wave of Chinese interest in matters spiritual. On this Easter Sunday, 237 new believers are baptised.

PASTOR JOSEPH GU: “We must admit that a person not only needs material goods such as food and drink – but also needs spiritual pleasure from music and dance – and to communicate with others”.

MCDONELL: As well as popularity, enthusiastic worshipers and a swanky new church building, Chong-yi has something else – government acceptance. The church is officially registered and ultimately answers to the state Religious Affairs Administration.

(to Pastor) “I know that sometimes people say you listen too much to the government. Are they right?”

PASTOR JOSEPH GU: “If we don’t have contact with them how can they hear the gospel? Actually, they’ve helped us. In Hangzhou for example the government has helped us build this church – and also another one”.

MCDONELL: But elsewhere here in Zhejiang Province relations between evangelical Christians and the Government have not been so rosy. Zhejiang in the country’s affluent South East is a hub of Christianity. In some cities here it’s estimated that one in ten people are Christians. The reason the real figure isn’t known is that there are two types of churches in China, official sanctioned and underground.

The latter are also called “house churches” because they meet in informal locations. They’re known as “underground” because to be a member is to belong to an illegal body and the authorities are wary of any group that organises any type of activities without government control.

So when we try and make contact with these underground churches, we start to see the same people hanging around us wherever we go. From the moment we arrive in this province we’re being watched, presumably because the authorities knew we were coming after having tapped our phones and read our emails. Every trip to the shop, every walk down the street means being tailed by plainclothes agents. And though we have a lot of new friends, some of these faces will start to become very familiar.

Driving also means being followed by the black Hondas of the local security services. At one point, we’re tailed for four hours in between cities and no matter what obscure part of this province we visit, they go with us.

You might think that around 2 dozen officers using 6 cars would be what you’d need for say a major homicide investigation or to break up a drug ring, but that’s the number of plainclothes agents we’ve spotted so far who’ve been tailing us down here.

So the Chinese Government is prepared to throw that level of resources into monitoring a few journalists who’ve done nothing more than try to make contact with some underground Christians.

Despite the security presence, an “underground” church leader agrees to meet us. We warn him that we’ll draw the secret police to his flat and indeed that’s what happens, but he says to come anyway.

PASTOR ZHENG DATONG: “We believe human beings are all corrupt and so, we need God’s blessings. We are evangelists”.

MCDONELL: Seventy-year-old Zheng Datong is a pastor at a house church in the city of Wenzhou. He takes a considerable risk by speaking to us.

PASTOR ZHENG DATONG: “Christianity propagates the existence of god, charity, love, virtue – and is against corruption. So it’s possible these corrupt officials are threatened by it”.

MCDONELL: He says people join house churches for all sorts of reasons – some are unhappy with the operation or doctrine of official churches. Some are wary of their government connections. In Pastor Zheng’s case, this choice has led him and his family into conflict with the authorities.

PASTOR ZHENG DATONG: “In the 1980s, things were all right but the 1990s were a bit difficult. I had some problems in 1994 and also in 1997”.

MCDONELL: “What kind of problems?”

PASTOR ZHENG DATONG: “Imprisonment as a result of my beliefs”.

MCDONELL: “So are you afraid now?”

PASTOR ZHENG DATONG: “Now we have nothing to be afraid of.

MCDONELL: “Why is that?”

PASTOR ZHENG DATONG: “Because God is with us and we are not doing anything bad”.

MCDONELL: Zheng Datong says he has nothing to be afraid of, but throughout our interview, secret police gather outside his house. He’s not keen to expose his congregation to this type of pressure so we’re not able to film one of his services. Pastor Zheng says in the past, governments have misunderstood house churches like his and that actually Christians and the Communist Party have much in common.

PASTOR ZHENG DATONG: “The lonely and vulnerable are most important. For example, love between people, charity, caring about others apart from ourselves. I think the Chinese Government also likes and advocates these ideas”.

MCDONELL: It’s estimated that there are a million Christians here in Wenzhou City alone, many of them in unofficial churches, yet we’re unable to film an underground service here because of the constant presence of the authorities.

After being pursued for five days we decide to go up and ask these agents why they’ve been following us. On this day they’re waiting for us in the foyer of our hotel like they have been every day.

(to agents) “Hello there. Why have you been following us?”

AGENT: “What are you saying? What are you saying?

MCDONELL: “Why have you been following us? Who are you?”

AGENT: (slaps Stephen) “When did I follow you? Who are you?”

MCDONELL: “Who are you?”

AGENT: (lashes out at camera)

MCDONELL: “We don’t know who you are.”

AGENT: “Who are you? Why are you filming me?” (pushing Stephen)

MCDONELL: “Why do you… ?”

AGENT: (lashing out at Stephen) “I’m asking who you are. Who are you? Excuse me?”

MCDONELL: (to hotel staff) “Can you please ring the police?”

AGENT: “Why are you filming my client?”

MCDONELL: They clearly enjoy the anonymity of spying on others to being filmed themselves.

(in hotel foyer) Well we’ve just approached these people who’ve been following us and had quite an extreme reaction from them. Now we’ve asked the hotel people here to call the normal police to come here for our own protection and there’s no sign that they’re coming so we don’t know quite what to do. I don’t trust who these people are. Actually they’re going over to our car now to ask questions there so yeah we don’t know quite what to do.

Outside the hotel the pushing and shoving continues as we wait for the uniformed police. The official story, which will be conveyed to us by the local authorities – is that these men were having a simple business meeting in the hotel when we interrupted them, that they’re not government agents and that they haven’t been following us – but our footage doesn’t lie.

Here’s one man in the foyer of the hotel and here he is watching us in the city the day before. Here’s another in the hotel and here he is also following us in the city. We’re given a government directive to erase our footage because apparently we’ve unfairly accused these men, but we manage to hang on to it.

As we’ve found, getting inside an underground church can be very difficult but we try again, travelling to the far south of China to the sprawling city of Guangzhou. This time there are no telephone calls or emails prior to our visit. We just turn up.

Well it may not look like it but amongst these backstreets, which are just rammed with apartment blocks, there’s said to be an underground church, which can hold a thousand people. So we’re here to try and find it.

We reach the house church run by Samuel Lamb. This eighty six year old preacher has spent a good part of his life getting into trouble because of his quite dogmatic beliefs. But his popularity has only grown.

PASTOR LAMB: “We used to have 400 believers, then 900… 2,000… and now it’s 4,000”.

MCDONELL: Pastor Lamb preaches in one hall, then via a network of televisions he’s carried through a rabbit warren of rooms. This honeycomb of a church services thousands of believers by having multiple gatherings but before the 1980s life wasn’t as easy for Samuel Lamb and his congregation.

PASTOR LAMB: “In gaol I worked in a coal mine for fourteen years. Many years in Guangdong and then they moved me to North China. Worked in the coalmine”.

MCDONELL: “Now why did they send you to gaol? What did the government send you to gaol for?”

PASTOR LAMB: “Oh they said I was anti-revolutionary because I preached the gospel (laughing) ‘Oh you are anti –revolutionary’.”

MCDONELL: Pastor Lamb says he has been asked by the authorities to officially register his church but he refuses.

PASTOR LAMB: “Obey the government. If not mixed up with our faith, we obey. If something against our faith, not obey”.

MCDONELL: Samuel Lamb says he won’t merge with the registered churches because they’re not real believers and they’re controlled by the government. Theologically, he says this means restrictions on preaching about the second coming of Christ, a big theme of his. He says that because oil is about to run out, the world will end soon – that earthquakes, tsunamis and even the existence of the modern state of Israel, all prove that Jesus will return in just a few years time.

Pastor Lamb also says it’s been years since his church has been raided. He believes there’s in part a tactical reason for this.

PASTOR LAMB: “Oppression then more believers. Oppression then more believers. Now they do not bother us”.

MCDONELL: If these churchgoers are being left alone, that’s certainly not the universal experience at the moment. The country is in the midst of a major crackdown, going well beyond Christians. Calls on the Internet for China to copy Middle Eastern protests have led the authorities to pick people off the streets who are considered potential troublemakers. Christians are caught up in this.

In recent weeks, every Sunday, there’s been a massive police presence in North Western Beijing. This followed the naming of Zhongguancun shopping area as a site for outdoor church services.

Well we’ve been told there’s going to be a gathering of Christians somewhere around here this morning. These are people who used to have a house church where they could gather – now they’ve got nowhere to do it so they’ve said they were going to meet in the street to worship. They were supposed to do it at eight thirty, it’s now eight thirty and not a sign of them anywhere here.

There must be a thousand officers here, including riot police to stop the service from happening. We walk in to take a look. Police guard every vantage point. The area where the gathering was to take place is roped off like a crime scene. But despite the intimidation, worshippers from the Shouwang Church start arriving and as they do, they’re taken away.

Our presence is not welcomed by the Beijing Police.

POLICE WOMAN: (into radio) “In front of Xindongfang… found two journalists from the Australian Broadcasting Corporation…”.

MCDONELL: We’re told that to report in this part of the city, special permission is now required three days in advance. We’re asked to leave.

On this day many dozens of Christians are rounded up and taken away by the busload. They’re driven to a makeshift detention area. We filmed the detained Christians clapping and singing on board a police bus as they head off to an uncertain future. Some ten leaders from the Shouwang Church remain under house arrest, but the vast majority of these churchgoers have been released.

In material terms most Chinese would measure their lives today as considerably better than their compatriots of decades gone by, but there are those who are searching for something more and who won’t submit their beliefs to government control.

GUO SANJIAO: “If someone tells me not to believe in the Lord – well, this is not going to happen”.

SONG CAILIAN: “In the future, I’m sure many people in China will believe in Jesus”.

SONG CAIYING: “God will arrange for us and find a road for us”.

MCDONELL: The government here is very concerned about groups which can organise beyond its reach, putting certain believers and the state on what seems to be a collision course and it’s hard to see who’s more stubborn – the Chinese authorities or these evangelical Christians. Either way, a solution will be hard to find with neither side prepared to back down.

http://www.abc.net.au/foreign/content/2011/s3219470.htm

China Aid Contacts

Rachel Ritchie, English Media Director

Cell: (432) 553-1080 | Office: 1+ (888) 889-7757 | Other: (432) 689-6985

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.chinaaid.org